You probably have engaged in the game Two Truths and a Lie as a team icebreaker and we wanted to try our own version… see if you can spot the lie among the truths regarding educator evaluation:

- Race To Top (RTT) educator evaluation policies have had little to no quantifiable impact on either teacher performance or student achievement.

- Feedback has and continues to have a positive impact on performance, affect, and outcomes, with data to suggest that teacher perception of the importance of feedback remains significant.

- Redrafting educator evaluation policies and approaches given ESSA changes guarantees impact on teacher performance and student outcomes.

Statement A = Truth

Since 2010 school districts in over 44 states and D.C. have been implementing educator evaluation policies with little to no measurable effect on teacher performance and/or student achievement. Schools everywhere “are not necessarily making full use of teacher evaluations as opportunities for teachers to grow” (Rosen & Parise, 2017). Primary findings have identified such causes as:

- inappropriate design, frequency, and methodology of observations (Tuma et al, 2018, Cantrell & Kane, 2013) (e.g., using “formal” and “informal”),

- use of single observers (NCTQ, 2022, Cantrell & Kane, 2013, Campbell & Ronfeldt, 2018), and,

- a lack of training and support for observers (NCTQ, 2022).

In 2015-2018 as we were coaching instructional leaders and writing our first book, Feedback to Feed Forward we identified 3 core false assumptions that accompanied the RTT shifts, especially in regard to administrator capacity to coach, lead learning, and impact student outcomes. It was assumed, based on preparation programs and training that administrators received that they would be able to:

- apply the skills they learned to observation in the classroom,

- analyze the observed practice of a teacher against a set of teacher performance standards and determine the potential impact on students, and,

- provide feedback that would directly impact teacher effectiveness.

Nearly 300 Teachers of the Year were surveyed and “fewer than half of respondents (49%) indicated that their observers were well-trained in conducting classroom observations” and “forty-two percent (42%) of respondents perceived their evaluation system as focused primarily on ‘getting a score or rating’ rather than on professional growth” (Goe, Wylie, Bosso, & Olson, 2017, p. 2) (Tepper & Flynn, 2019). It is important to note, not all elements/specific practices within systems are void of impact.

Statement B = Truth

While sentiments about evaluation vary, research is in agreement about the power and necessity of formative feedback from supporting research. Frequency and design of feedback are commonly identified as important factors leading to positive perceptions. Feedback has a direct impact on teacher self-efficacy and schoolwide collective efficacy, both of which have a direct influence on student achievement (1.39) (Hattie, 2023).

- Teachers tend to show high levels of perceived impact related to frequent formative feedback (RAND, 2018).

- 3 out of 4 teachers in their first three years of service show the highest levels of perceived impact while veteran or tenured staff who reported receiving specific evaluation feedback also reported higher teacher self-efficacy (Smith et al, 2020).

Unfortunately, most current evaluation-driven systems of feedback have not included frequent formative feedback.

Statement C = Lie

Proposed and ongoing ESSA legislative changes can have a positive impact. The untruth here is that a new policy alone is our answer to ensuring teachers are supported in the difficult endeavor of creating equitable and accessible learning for all students. We must learn from our mistakes (albeit well-intended) that include:

- limited alignment of policies to known effective practices associated with performance management systems (Bleiberg, et al, 2021),

- unnecessary implementation of policies and structures that distract from more impactful practice (Bleiberg, et al, 2021) (e.g., timelines, forms to complete).

As a result of decisions made and actions taken, evaluation policies of the last decade have:

- Generated a compliance mindset,

- Resulted in inflated ratings and inaccurate assessments of teacher effectiveness,

- Led to feedback practices being implemented and viewed as isolated “evaluation” events, and,

- Required new practice, training, systems, and structures but quickly became an unfunded mandate

In 2019, based on our work and the 2015 MET Project, we wrote: “what ended up accompanying the introduction of these systems was training that ensured evaluators were successful in checking things off a list, tracking test scores, tagging evidence, and filling out forms. These skills took precedence over insight, reflection, coaching, growth, and a focus on gains in student readiness for the future. These realities ensured compliance but did not build the potential for continuous improvement of student success.”

Policy alone is never the answer for one important reason — “culture eats strategy [and policy] for breakfast” (Drucker, 1959).

The Truth and Nothing But the Truth

We must ensure new approaches to allow schools and districts to cultivate a culture of learning and create the conditions for success as outlined in Wallace Foundation report (Grissom, et al 2021) and purposefully shift the role and perception of observation and feedback.

Districts that take the steps to shift the focus and attention of their evaluation models and systems to ensure effective feedback for growth rather than using designs that emphasize accountability have a higher rate of impact.

To help in designing/identifying the best performance improvement system, consider the research and the possibilities. What if…

- The foundation of educator evaluation was built and implemented on a framework of growth, instead of inspection of practice?

- Supervisor training was designed to support the development of an instructional leader instead of just an observer of classroom practice?

- The focus of observation became what, how, and if students were learning, instead of just whether or not teachers “performed” at proficient levels? (Tepper and Flynn, 2019)

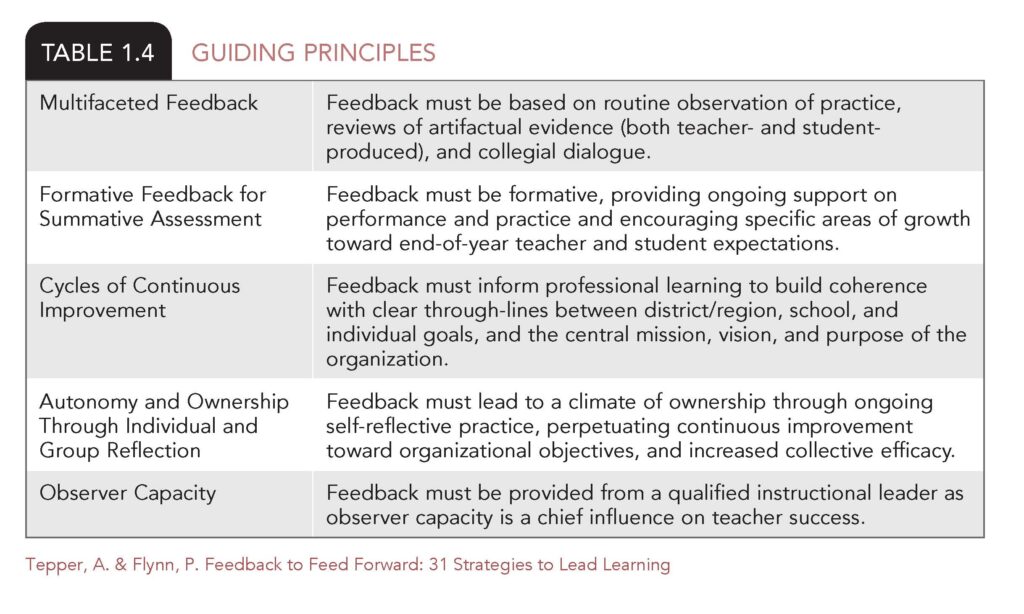

Districts can begin a shift by assessing how their district addresses/applies the guiding principles (from our first book) that can help shift mindset, culture, and outcomes.

Two Truths and a Lie icebreakers can build bonds and afford opportunities to examine preconceived notions or assumptions, refine conclusions, and alter perspectives. For more than a decade, mindsets and beliefs about evaluation have stifled any real opportunity for change. As states, districts and schools examine their own policies and systems and shift to more effective classroom practice and student outcomes, the call to action will be–follow the research and create systems based on supporting adult learning through feedback rather than to rebuild structures of inauthentic accountability.

Supporting educator growth is possible. If you are going to construct 2 Truths and a Lie for your school or district as it relates to improvements in this area, what would they be?

Cited Sources

Bleiberg, Joshua, Eric Brunner, Erica Harbatkin, Matthew A. Kraft, and Matthew Springer. (2021). The Effect of Teacher Evaluation on Achievement and Attainment: Evidence from Statewide Reforms. (EdWorkingPaper: 21-496). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University: https://doi.org/10.26300/b1ak-r251

Campbell, S. L., & Ronfeldt, M. (2018). Observational evaluation of teachers: Measuring more than we bargained for?. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1233-1267.

Cantrell, S. & Kane, T.J. (2013). Ensuring Fair and Reliable Measures of Effective Teaching: Culminating Findings from the MET Project’s Three-Year Study. Seattle, WA: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Policy and Practice Brief, Measures of Effective Teaching project.

Drucker, P., 1959. Work and Tools. Technology and Culture, 1(1), p.28.

Goe, L., Wylie, E. C., Bosso, D., & Olson, D. (2017). State of the states’ teacher evaluation and support systems: A perspective from exemplary teachers. Executive summary. ETS Research Report Series, 2017(1), 1–27. doi:10.1002/ets2.12156. Retrieved from https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-17-30_Executive_Summary.pdf

Grissom, Jason A., Anna J. Egalite, and Constance A. Lindsay. How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research. Wallace Foundation, February 2021, https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/how-principals-affect-students-and-schools-a-systematic-synthesis-of-two-decades-of-research.aspx.

Levitan, S. (2022). How are districts observing and providing feedback to teachers? Retrieved from National Council on Teacher Quality: https://www.nctq.org/blog/How-are-districts-observing-and-providing-feedback-to-teachers

MET Project. (2015). Seeing it clearly: Improving observer training for better feedback and better teaching.

Seattle, WA: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved from http://k12education.gatesfoundation.org/resource/seeing-it-clearly-improving-observer-training-for-better-feedback-and-better-teaching/

Prado Tuma, Andrea, Laura S. Hamilton, and Tiffany Berglund, How Do Teachers Perceive Feedback and Evaluation Systems? Findings from the American Teacher Panel. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10023.html

Rosen, R., & Parise, L. M. (2017). Using evaluation systems for teacher improvement: Are school districts ready to meet new federal goals? [Online pdf]. Retrieved from https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/iPD_ESSA_Brief_2017.pdf

Smith, E. C., Starratt, G. K., McCrink, C. L., & Whitford, H. (2020). Teacher Evaluation Feedback and Instructional Practice Self-Efficacy in Secondary School Teachers. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(4), 671–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X19888568

Tepper, A., & Flynn, P. (2019). Feedback to feed forward: 31 strategies to lead learning. Thousand Oaks. CA: Corwin

Tuma, A. P., Hamilton, L. S., & Tsai, T. (2018). How Do Teachers Perceive Feedback and Evaluation Systems?: Findings from the American Teacher Panel. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10023.html.

Leave a Reply